History of Preston 1780 to 1900

Preston developed its cotton industry from around 1780. Early production was based on Hargreaves 'Spinning Jenny' and Cromptons 'Mule' which required hand, horse or windmill to power it. The reason for this being that Preston had no fast running streams so the Arkwrights water frame could not be used.

Names such as Horrocks are still known to this date. It is over 200 years since John Horrocks died. One of the major founders of cotton in Preston. The old wall that stood on London Road facing New Hall Lane was Horrocks mill and more recently became a Sainsbury Homebase. This factory was a massive undertaking filling a large area close to the centre of the town. A model is in the Harris Museum, Discover Preston display. High brick walls against the street were typical in Preston.

Photo:

Stephen Simpson Ltd founded in 1827, closed in 2009. Avenham Road, Gold thread embroiderer.

Several of Preston's finest buildings came from the era of the cotton moguls. Harris Library and Institute, Miller Arcade, Town Hall (destroyed by fire). The parks; Avenham, Miller, Moor, Haslam and Ashton were built around the mid-1800's largely to employ people hit by the cotton famine of the 1860's.

The first spinning mill was built by William Collison about 1777 in Moor Lane. In 1785 John Watson built a factory in Lower Penwortham. In 1785 a factory in Dale Street was built which was bought by John Watson in 1803.

John Horrocks built his first Preston factory in Dale Street in 1791. It was called the 'Yellow Factory' after its faded whitewash and was so large that its sponsors panicked. By 1820 Preston had around 12 mills and by 1846 there were 42 employing 20% of the population. In 1845 the largest power loom weaving shed in the world was built by William Ainsworth. By 1850 there were 64 mills. The peak of Preston's growth was being reached fairly soon in the Lancashire Cotton cycle as towns like Oldham built newer and larger mills later.

Winckley Square 1799

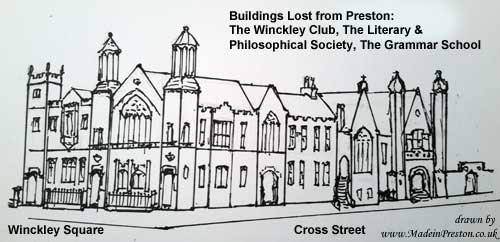

In 1799 Mr Cross bought a field from Mr Winckley and created Winckley Square. An area for the gentry, set away and upwind of the industry that was changing the town. The houses were all built to order over a period of 50 years by the wealthy of the day. The Horrocks brothers were wealthy enough to live out of town, at Penwortham Lodge and Lark Hill. The area also hosted the main educational establishments, Preston Grammar, Catholic College, Dr Shepherds Library, the Literary and Philosophical Society and gentlemens club, most of these were knocked down in the 1960s. The square originally took the form of flower beds and patches of trees but later was apportioned to the houses for gardens before returning to an open area.

19th Century

The late 18th Century and early 19th Century was a time of war, with Britain on one side and France, Spain, Holland and America on the other. Shipping across the Atlantic was threatened by privateers who would take the cargo and the ships. Ships formed convoys to protect themselves and the main shipping port became Liverpool as it was large enough to harbour a convoy. Lancaster began to decline as a port. Cotton and Sugar being the main cargoes inbound. The Royal Navy was expanded and became master of the seas to underpin Britain's trade. The Battles of Trafalgar, Waterloo and American War of Independance settled the situation and trade was able to flow better. Britain also looked towards Asia for trade.

In 1802 the Guild Merchant celebration was taken over by the cotton industry and adapted to the changes in the town.

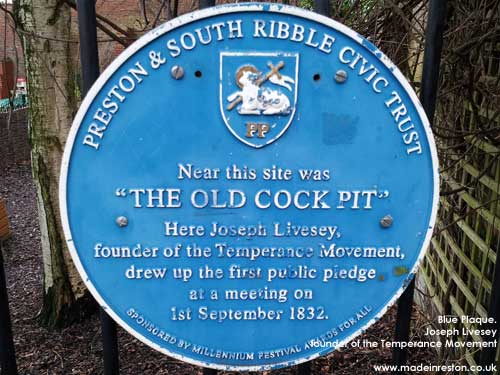

Photo: Blue Plaque. Joseph Livesey, founder of the Temperance Movement drew up his first pledge in Preston 1st September 1832. The plaque is at the back of the Minster. There are several sites in Preston related to his activity.

In 1821 John Jenkinson painted the view below from Penwortham. Wheat harvesting would make it approximately a September view. The factory chimneys, windmills, church spires and in the background on the left the hills. In late 2015 this painting was subject to an appeal for funds to conserve it and it's now back in the Harris with some etchings of a similar scene. This photo is pre-clean up, it's actually quite a bit darker than the photo below and a small patch of sky has been cleaned to show what is beneath. See the Harris page for the later version.

An Ordnance Survey map of 1840 shows how the town developed. The central core of housing contained an orchard where the covered market stands, so Orchard Street led to an orchard. The Corn Exchange which became the Public Hall was a 2 storey market with a central courtyard area. At the back was the canal wharf with the Tram Road going to Avenham and the Leeds Liverpool Canal. Of note at this time are the mills which are not yet surrounded by housing except for Horrocks Yard Mill. For example Greenbank, Moorbrook, Brookfield, Ribbleton Lane Mills are in fields. Deepdale Road is there and there is a House of Recovery where the hospital used to be and a bit further out is the Workhouse surrounded by fields. Another item on this map is that the electoral wards are called; St Johns, St Georges, St Peters, Trinity, Christchurch and Fishwick - the church obviously played a big part. Another feature is that the route over the river at Penwortham uses only the little old bridge that is at the end of Broadgate. The railway line south, the Tram Road bridge and London Road / Walton Bridge being the other crossings.

Photo of the currently named 'Cotton Court' on the site of Horrocks Mill complex off Church Street, this was formerly Starkies wire making mill:

The population of Preston grew from 12,000 in 1800 to 70,000 in 1850 and 100,000 by 1880. The housing development was largely ad hoc with building of terraced houses around mills. No made up roads that became full of mud and open sewage. These conditions gradually spread. Church Street, Avenham Lane, New Hall Lane, Friargate all contained closely packed houses with ginnels, industrial buildings, slaughterhouses. Except for Winckley Square with its pleasant Georgian houses.

This population growth also demanded an increase in religious establishments and the first half of the 19th century saw a period of large church building. In 1840 there were 7 main CofE churches, 4 RC, 13 classed in 1840 as dissenters (which also at that time included RC), which were: 2 Independents, 2 Wesleyian, 2 Baptist, Unitarian, Friends, Primitives, Episcopalians, Huntingdonians, Scotch, Sandemanians. At that time St Andrews wasn't considered as in Preston(check?).

The growth in population was noted by the army who transferred the 20th Fusiliers from Devon to Lancashire in 1798, initially to Preston and recruited 300 new soldiers in the town. They later changed name to the Lancashire Fusiliers and moved to Bury where there is an interesting and modern Royal Fusiliers museum.

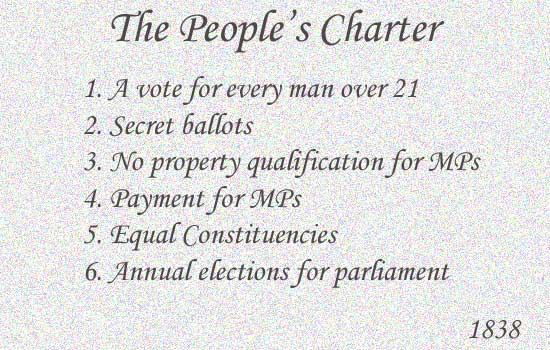

In the period 1836 to 1848 a group called the Chartists campaigned for greater rights for workers. Protest meetings were held all over the country. In Preston troops fired on a group on Lune Street. Fulwood Barracks was built as part of the national enforcement of the law. In 1838 the People's Charter was written containing 6 demands.

The statue below marks the place where troops shot on chartist protestors in 1842 Preston, killing 4 after they had been read the riot act and were stoning the troops.

Fulwood Barracks, anti-chartist enforcement.

Joseph Livesey, temperance pioneer

Born in Walton Le Dale on the boundary of Preston in 1794. Spent his childhood at a hand-loom in a damp cellar and recorded;

(abridged) 'the cellar was my college, the breast beam my desk, and I was my own tutor. Many a day and night I laboured to understand Lindley Murray, an English Grammar, by indomitable perseverance, without aid from any human being.' For hours he did what no-one else could do which was read and weave. He read by the light of the last few embers.

Livesey travelled to Bolton and Manchester and wrote of the drunkenness. Drinking being the working mans favourite recreation and his favourite sport being fighting.

In May 1838 his paper the Moral Reporter reported a 'purring' match near Bury where 2 men stood naked except for iron toed boots studded with jagged nails. Fair kicking being shins and knees.

Renouncing drink had been a topic for some time, Rev Cowherd of Salford in 1809 and Joseph Brotherton of Salford in 1819. In 1831 Joseph Livesey launched the Moral Reformer and said a more resolute spirit was needed than moderation. In 1832 Joseph Livesey urged a pledge of 'total abstinence' and that he had tasted no alcohol since commencement 1831.

Heated discussion took place in Preston about the wisdom of total abstinence. In August 1832 Livesey and John King signed a pledge to that effect. They were joined by 5 others and the seven men of Preston soon grew and were joined by Richard 'Dicky' Turner a reformed drunkard. At a meeting in Preston in September 1833 Turner gave a passionate speech and declared that nothing but teetotal would do. The audience erupted and Livesey called 'that shall be the name Dicky'. Livesey later said 'if a suitable word was not at his tongue end he (Dicky) would coin one'.

There was opposition in Preston but 2000 were teetotal by the end of the year. Livesey said 'Preston, was regarded as the Jerusalem of teetotalism from which all roads led'. He described how he and six companions with a horse and cart, 9,500 tracts of the pledge and a white flag bearing the temperance motto set out in July 1833 to convert the manufacturing districts. They went all over Lancashire and attracted large enthusiastic audiences. By the end of 1834 28,000 had signed the pledge. Temperance Societies were set up all over Lancashire and large gatherings in theatres took place.

Drunkenness continued to be a major problem until well into the Victorian era.

(all of the above on Joseph Livesey from one book Lancashire the First Industrial Society C.Aspin, Helmshore History Society 1969 - a great read)

Candles lit the early mills until in 1805 a mill in Salford was lit by gas. Preston got its own gas company in 1816, quite early, Accrington was 1840. It was common for there to be votes on whether to have gas lighting or keep the darkness and in some places darkness won even though it seemed most people were very excited about the prospect of lights.

Gas had another benefit enabling the use of balloons. At the Preston Guild of 1822 a balloon was demonstrated and in a high wind it reached Whalley where it was meant to land. After much difficulty Mr Livingstone fell out and the balloon went a further 6 miles. In 1849 a large crowd turned out to watch a balloon fly over the Corn Exchange but it hit the weather vane tearing a hole and almost hit some spectators who had gone onto the roof.

In the 1840s the earliest electric lights were being demonstrated but were deemed too expensive. An experimental electric light was shone from a hill near Manchester with observers all around saying how beautiful it was.

From the 1780s the seaside became a place to visit, mainly for the middle classes. Transport was horse and horse and cart and accommodation was very rough with locals able to rent out haylofts and hay beds. Southport, Lytham, Blackpool, Fleetwood, Morecambe were just a few houses. By August Bathing Sunday 1828 every cart and horse in Preston was in use towing excessive numbers of people along the Clifton Toll Road to Lytham and Blackpool. It changed the character of the resorts with some complaining about the lack of decorum and loss of seclusion. Preston people went to Blackpool, Manchester people to Southport.

In 1840 the railways from Preston to Fleetwood and Lancaster brought a big increase in visitors. In 1842 2364 Sunday School Scholars and their teachers travelled from Preston to Fleetwood in 27 open carriages decorated with colours and mottoes. They sang hymns at Poulton Le Fylde where they stopped en-route attracting a crowd. (Editors note: seems a very beautiful moment, although the number of carriages seems small for so many people).

The poor people of Preston were treated to an annual journey to Fleetwood in the 1840s including a boat trip and use of baths at the North Euston Hotel and sea bathing.

In 1846 the railway to Blackpool opened and mill outings from all over Lancashire flooded to the resort with great excitement. By the 1850s some 200,000 were travelling from Manchester alone, to the seaside. The Preston Pilot reported in 1851 that Blackpool would decline if respectable visitors were driven away. Southport and Morecambe got their rail links in the 1850s with Morecambe being popular with Yorkshire people.

(much of the above from one book Lancashire the First Industrial Society C.Aspin, Helmshore History Society 1969 and using extracts from the Preston Pilot and Preston Chronicle - a great read)

Edmund Robert Harris

Edmund Robert Harris is perhaps Preston's greatest citizen, his legacy left the finest buildings in Preston and care and education for the people of Preston.

Born 6th September 1803 and baptised 19th November 1803, child of Robert Harris, 1764-1862, and Nancy Harris (nee Lodge) 1774-1837.

His father Robert Harris was the Headmaster of Preston Grammar School, from 1788 to 1835, which was located in what is now Arkwright House, where the family lived, and Pastor at St Georges Church.

Edmund had a brother Robert who died at birth in 1802. Also a brother Thomas 1805-75, and a sister Ellen Elizabeth 1807-49.

When his father Robert ceased to be headmaster at PGS the family moved to Ribblesdale Place.

Edmund and Thomas worked at the family solicitors. It has been said Edmund was rather finicky (my word) and nervous but public spirited. After the death of their father they moved to Whinfield House which was on the corner of Pedders Lane and what is now Riversway. A large house overlooking the Ribble valley and built in the grounds of Ashton House. After the death of Thomas, Edmund inherited the family fortune and on his death bequeathed most of it for the good of Preston.

During his life, Edmund, having been told of sickness in the town donated ?7000 towards medical care.

On the 27th May 1877 Edmund died and on the 1st June he was buried at St Andrews in Ashton. Edmund's will left ?311,805 8s 3d for the following, other funds were left for his staff and others:

?500 to Preston Industrial institutions for the employment and education of the blind.

?3000 to the foundation of the Harris Scholarships at the Preston Grammar School.

?7000 for the enlargement or improvement of churches or chapels of the Church of England in Preston or the erection of schools for elementary education in the town.

?78,564 8s 3d for the Harris Institute and Tehcnical School.

?100,000 for the Harris Orphanage, Fulwood.

?122,466 for the Harris Free Library and Museum.

It was 1880 before rules became established about such taken for granted things as a front door step so that the ground floor was above the level of the road, backyards containing a water closet with an access along the back of the house. In the late 19th Century Preston was for 15 years the town with the highest numbers of infant mortalities in Britain with figures of over 250 deaths per 1000. Surprising that with development of transport and communications; canals in 1790's, railways in 1830's, telegraph in 1850's, docks in 1880's, sporting clubs in the 1860's and fine public parks that life wasn't more amenable.

Major Building

The latter part of the 19th Century brought some significant buildings; the Town Hall 1862 (burnt down 1947), Covered Market in 1875, Harris Library and Art Gallery finished in 1893, Miller Arcade finished 1898 so Preston was taking on a look that is familiar today.

Wealth enables fine public buildings. It seems this region could never again have such prominence, so we must protect our heritage.

The Town Hall was built in the period 1862-6 on the place of the existing town hall next to the Flag Market. It was a Gothic style similar to many built in that era and affordable through the wealth of cotton. The architect was Sir George Gilbert Scott a leading designer of the time who also built St Pancras station in London. Preston Town Hall though not too grand in size, unlike Manchester Town Hall which was built later at enormous cost, had a lot of fine detail and was considered one of the best in the UK. It had the look of a church with a clock tower like Big Ben. It is said that if Preston had waited a bit longer a grander hall would have been built. Unfortunately it burnt in 1947 and the council voted to have the remains destroyed, to be replaced by Crystal House, a much derided object.

The Harris Museum was built adjacent to it in the late 1880's to a classical style by a local architect James Hibbert. The classical style was said to be out of date by some at that time, although it's now a jewel, Grade 1 listed.

The 1882 Guild took on a more regional and national view with mayors from the surrounding towns and cities invited.

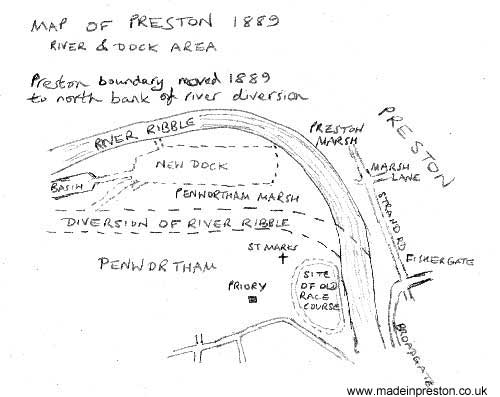

Docks in 1892 required diversion of the River Ribble and a change to the boundary of Preston.

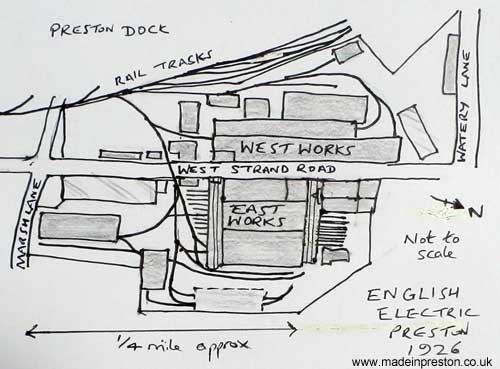

The Dick Kerrs Works, later English Electric, GEC and BAC was another large undertaking next to the dock in the late 19th Century.

Image drawn as simplified version of map in English Electric Trams by Geoff Lumb, see trams page.

Photo below: This was once the only bridge over the River Ribble at the west end of Preston. At the end of Broadgate. Quite a nice bridge, now restricted to foot.

The Mexico and the Ribble Lifeboat Disaster 1886

Photo: view across the Ribble at low tide from Lytham old Lifeboat Station. The anchor is similar to the one on the Mexico and was found in the Ribble.

1887, a wrecked boat, the Mexico, a German sail ship, was salvaged and repaired in Preston after sinking in the Ribble estuary.

Previously in December 1886 it set off from Liverpool to Ecuador and due to the northwesterly couldn't get out of the Irish Sea. It dragged anchor until it became grounded and began to break up at night in the mouth of the River Ribble in a bad storm.

Distress signals were seen at 9pm and at 9.15pm the St Anne's gun was fired. Three lifeboats were out from St Annes, Lytham and Southport rowing and using sail in heavy seas.

Southport's 'Eliza Fearnley', 16 crew needed a 3 mile road journey and was launched at 11pm and arrived at the wreck at 1am but was capsized and washed to shore..

St Anne's 'Laura Janet', 13 crew left at 10.25pm and was found near the Palace Hotel at Birkdale.

Lytham's 'Charles Biggs' 13 crew left at 10pm and arrived at 12.30am and picked up the 12 crew who were tied to the masts. They rowed back and were watched by people on Southport pier who thought it was their lifeboat returning but it rowed past arriving at Lytham at 3.15am. At 10.30am later in the day the Charles Biggs was re-launched to search for the St Anne's boat.

The Samuel Fletcher (the first Samuel Fletcher) was also launched from Blackpool to search later in the day and was almost lost enroute.

Two lifeboats lost with 27 crewmen only 2 surviving, the biggest loss of lifeboat crew in the UK. There were 16 widows and 50 children of the crew. The funerals were held at St Cuthberts Lytham, St Anne's Parish Church, Layton Cemetery Blackpool, Southport Duke Street Cemetery.

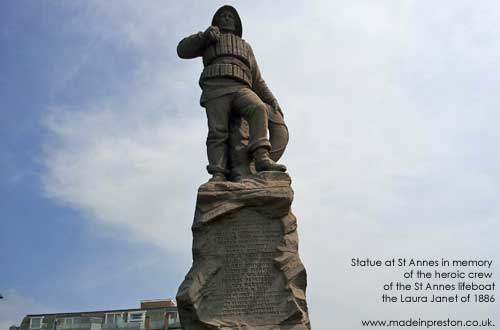

The enormous bravery of these men is commemorated at St Annes with the lifeboat memorial, a statue close to the pier. The Lytham coxswain Thomas Clarkson getting an RNLI Silver Medal. 30,000 people attended the first Lifeboat Saturday Fund event in Manchester which was started as a result of the disaster by St Annes businessman Sir Charles Macara. This eventually became the Lifeboat Flag Day run by the RNLI.

Photo above. In St Cuthberts churchyard at Lytham a grave headstone is inscribed: 'In memory of James Bonney, aged 21 years. Nicholas Parkinson 22yrs, Richard Fisher 45yrs, Oliver Hudson 39yrs, James Johnson 45yrs, John P Wignall 22yrs, William Johnson, coxswain 35yrs. Seven members of the crew of the St Annes Lifeboat "Laura Janet" all of whom perished during the storm on the night of the 9th December 1896, in a noble attempt to rescue the crew of the German barque "Mexico". This gravestone is Grade II listed by English Heritage.

'

'

Photo above. At St Anne's on the Sea a statue stands on the promenade inscribed. 'This monument was erected by public subscription in memory of William Johnson - coxswain, Charles Tims - sub coxswain, Oliver Hodson - bowman, Thomas Bonney, James Bonney, Nicholas Parkinson, James M Dobson, James Johnson, Richard Fisher, John P Wignall, Thomas Parkinson, James Harrison, Revben M Tims. The crew of the St Annes Lifeboat who lost their lives in a gallant attempt to rescue the crew of the German barque 'Mexico' wrecked off the Southport on the night of the 9th December 1886'.

In reality there are no statues big enough for such men.

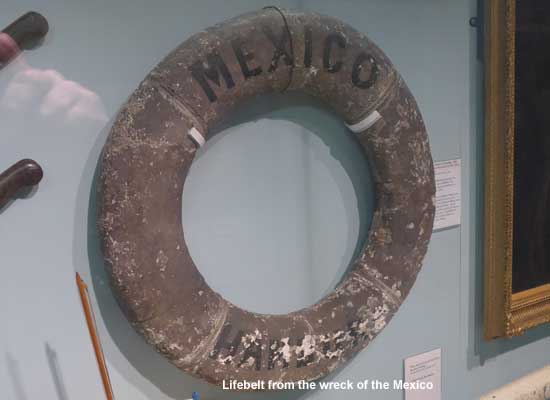

At the Atkinson Museum Southport is a lifevest of a similar style to the one worn and a lifebelt from the Mexico.

South Lancashire Regiment march to war

Photo: Fulwood Barracks, Preston, built 1842 to fight the Chartists.

On the 30th November 1899 1100 men of the South Lancashire Regiment and 150 reservists of the North Lancashire Regiment who had been based at Fulwood Barracks marched through Preston to the railway station.

This was quite an occasion in Preston said never to have been repeated with such exuberance. The people of Preston had donated a pipe and one pound of tobacco to each of the troops and as they marched, accompanied by bands, down Deepdale Road, Church Street and Fishergate the roads were packed with thousands of well wishers. They boarded the train which was to take them to Liverpool and every station on the route was packed with well wishers. At Liverpool they boarded the SS?Canada and sailed to South Africa to the Boer War.

Another battalion of the South Lancs was said to have left Warrington watched by 80,000 people. (ref. Red Roses on the Veldt, Lancashire regiments in the Boer War 1899-1902 by John Downham).

Photo of the Boer War Memorial on Avenham Park